David Levine and the power of political caricature

Soon after joining Op-Ed as art director, I set off an unseemly spectacle. An essay that accused Henry Kissinger of manifold war crimes was to run on Sunday. William Pfaff, International Herald Tribune columnist and influential foreign policy author, had written an authoritative text that called for bold art.

Though I was a naïf from California, new to New York and the Times, I was acquainted with the work of David Levine, whose caustic caricatures in the New York Review of Books would, I thought, enhance Pfaff’s prose. Levine jumped at the chance to portray the famed statesman whom he despised.

Henry Kissinger by David Levine, 1979

Levine´s drawing was a satiric masterpiece. Tattooed on the diplomat’s back are the hallmarks of his career: Shoulder hairs become Arabic script, bombs fall on Cambodia, Vietnam darkens, and “Richard” shares forearm billing with “Mother.” Kissinger´s cheeks feature the Shah of Iran, a Chinese dragon, and a holstered gun.

Glowing with pride, I presented the superb spoof to Charlotte Curtis (Op-Ed´s top editor and the person who hired me). Curtis turned up her nose.

“That’s awful!” she sneered.

“It’s kinder to Kissinger than the Pfaff text,” I said. Curtis squeezed tight her fluttering eyelids as I struggled to salvage the drawing: “I’ll try to negotiate a mid-dragon crop.”

“That’s not it,” she snapped. “It’s the excessive midsection flesh.”

Curtis spun around in her chair. With withering finality, she announced, “It’s a cheap shot.” Having failed to meet Times standards, all I could do was apologize profusely to the artist.

“Send it back,” was Levine´s icy reply.

I returned his original and asked the Times bookkeeper to send him a check for the full price of publication instead of the usual 1/2 “kill” fee.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. The Village Voice’s December 24, 1979 cover featured a detail of the killed drawing with the line, “Too Cheeky for the Times.” Inside, the full Kissinger drawing graced an article that defended the artist and attacked the art director (by name). At the end of the article was a note that read, “Matthew Levine, who works at Time magazine, is David Levine’s son.”

The son quoted me as saying, “You can draw whatever you want” and his father as saying, “I told her to tell her editors to never, ever, ever contact me again.”

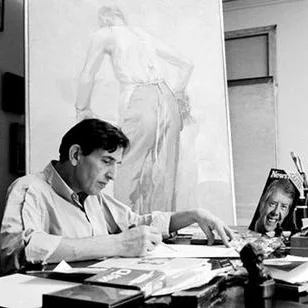

David Levine circa 1970-1980

In my over-excitement at the new job´s thrills, I made a huge mistake in giving Levine free rein. But the seasoned Levine was far from ignorant. His son’s reporting revealed that two of his father´s “caricatures, of Nixon and Koch, were rejected [also by the Times] due to the strength of statement in each.” And Levine himself later wrote me, “I expected exactly what transpired at the New York Times”

Since no artist likes to see a beloved piece languish, it´s not surprising when an illustration that was rejected by one publication appears later in another. I strongly suspect that Levine´s elaborately tattooed Kissinger (delivered quickly after I called him) was first rejected by the New York Review of Books.

In 1991, eleven years after the tattoo debacle, David Levine accepted a Times commission, thereby recanting his dire, “never ever” threat. By that time, after a decade as Op-Ed art director, I´d been fired by the fourth top editor I worked with, Les Gelb, who found me insubordinate. But he lacked the power to fire me from the paper; I simply switched to another section. Gelb, a heavy hitter who had come to the Times from the Department of Defense, would soon be fired altogether from the Times.

A year after Gelb left, Op-Ed´s new editor asked me back. The person who art directed Op-Ed between my two stints also had the bright idea of commissioning David Levine. This time, it was published. The outrage that its publication unleashed tortured the Times more than has any other illustration.

The Descent of Man, David Levine, January 1991

Since its 1970 debut in the Times, Op-Ed has found occasions to publish freestanding art. It was on one of these occasion, in the early days of the Iraq war, that Levine recanted. The subject was Saddam Hussein. His five-figure caricature ran, sans text, under the title, “The Descent of Man.”

Looking at it now, it´s hard to understand how the editors could have let it go. But let it go they did. And on the morning of publication, Arab-Americans telephoned in droves. They were so mad and so many that the Times was forced to record an apology.